Probably, the factor that distinguishes a student or amateur ensemble, of any kind, from an advanced or professional one is tuning and intonation.

While the following utilises one of the acoustical phenomena commonly used by string players during tuning, it will be of more benefit to leaders of wind ensembles.

Most teachers or conductors of amateur and student groups will be accustomed to tuning to a sustained note, usually A, or in the case of brass or wind bands, it could be a B flat. The problem with this is that many players will, consciously or unconsciously, compensate by correcting the pitch with the embouchure. Once the music starts, the tuning is ‘out’ again.

The following sequence for tuning instruments can provide a useful remedy for this. It can be a lengthy process initially, depending on the size of the group, but it speeds up as you and the players get used to it – and it pays dividends.

- Tune the first player to a digital tuner. This is optional because the main objective is to have the players in tune with each other not necessarily to the exact concert pitch, but of course you won’t want to be too far out.

- Have the first player play a short ‘open’ note. Short means about one second, but not staccato.

- Immediately, get the next player to do the same. You will find it is very easy to compare the pitches and give the necessary ‘pushing/pulling’ instructions to the players. After a while, this process can become quite quick.

- Go through this process comparing each of the players with the first, occasionally back-tracking to check those who have been tuned.

- When a section (for example, first clarinets) has been tuned in this way then have them play long unison note ‘forte’.

- Listen carefully and you will hear either beats, signifying that the section is not in tune or, when they are in tune, you should hear the octave above the tuning note ‘ringing’ out!

- Repeat the above with other sections until you are satisfied.

We hear the beats or octaves because of ‘sum tones’ and ‘difference tones’: When two notes are played simultaneously, we hear additional frequencies which are the sums of, and the differences between, the frequencies of the notes being played. This is a psychoacoustical phenomenon rather than a physical one. If the difference between the frequencies is just 2-3 Hz, then the difference tones will be below our hearing threshold, but they will generate ‘amplitude modulation’ of the basic tone leading to the familiar ‘wah-wah’ effect. If they are in tune, the clear octave above will be heard.

For the sake of clarity, let’s take A as an example. It is common knowledge that, in standard concert pitch, A = 440 Hz.

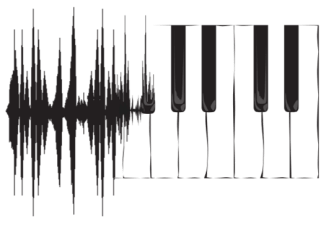

440 + 440 = 880 so the sum tone, ‘A’ one octave higher, would be heard. No difference tone would be heard since 440-440=0. This indicates that the note is in tune. The following short video provides a graphic illustration.

However, 440 – 438 = 2; one note is 2 Hz. flat, so ‘beats’ at the rate of 2 per second would result. A similar effect would be heard if the note was sharp. Of course, the above tuning procedure would enable the director to decide which!

Needless to say, the focus will turn to intonation (the players) rather than tuning (the instruments) once your rehearsal is under way.

As was pointed out above, this process can be quite time-consuming at first, but you will find that, once these tuning habits are well established and the players are encouraged to listen critically to, and correct, their own tuning, the whole procedure can be executed fairly quickly.

Not only will your ensemble sound more in tune, but a considerable improvement in the richness in the ensemble’s tone quality, due to the presence of combination tones, will result.