Excerpt from Instrumental Music Teaching by Robert Lennon

Given that playing an instrument stands to enhance young players’ educational achievement in so many ways, the question becomes one of how to keep them playing long enough to reap the benefits. The desire to play is usually, in the first instance, brought about by things such as liking the sound of a particular instrument, its appearance, its ‘image’, or even admiration for a particular player, singer or group. The Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music’s statistics also tell us that a considerable number of youngsters begin playing for no other reason than that one or more of their friends have started and they would like to try it too.[i] Whatever the initial impetus for a student’s starting to play, repeated ‘rekindling the fire’ of motivation will be essential until such time that the satisfaction they derive from playing is sufficient, i.e. when the motivation has become intrinsic. This is probably the most fundamental task facing any instrumental teacher.

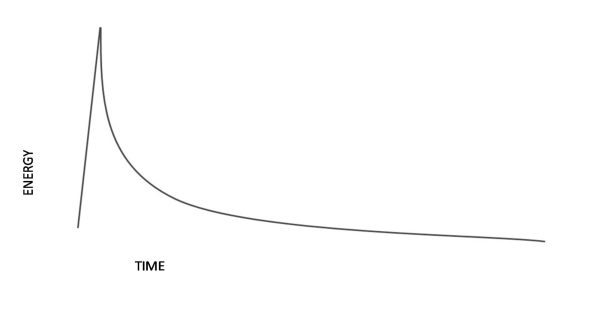

The natural trajectory of motivation, however compelling the initial stimulus, is downward. If one were to plot this on a graph, it would probably look something like an ‘energy loss’ curve or, in terms that are ‘closer to home’, the natural decay in the intensity of a note played on the piano.

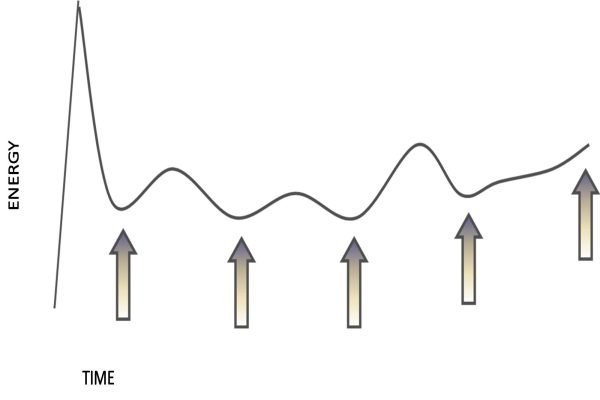

Looking at this trace of the piano ‘envelope’, we see that the onset of the energy is rapid – almost instantaneous but then almost as quickly, its intensity drops markedly leading to a more gradual decay. The similarities to, as well as the implications for, student motivation become clear: most begin with an explosion of enthusiasm but quickly become discouraged when the realities of how difficult their task could be, start to sink in. Imagine, for example, an instance where a child wanted to play the flute because she had heard an accomplished flautist play live at her school, or had heard recordings featuring virtuoso flautists, and been captivated by the sound. The onset of her motivation to play would, almost certainly, present itself as a surge of intense desire as opposed to mere interest. It is likely that when, during her first lesson, she attempts to form the embouchure and play a note, she is unable to produce anything she recognises as a musical sound at all. When she does succeed in making a sound, it is a world away from the sound that so excited her in the first place. At the same time, she suffers the alarming realisation that it is going to take a long time to achieve the quality of tone and fluency of fingering, articulation, etc. that she desires. This is exactly the kind of situation in which the thought, “I can’t do it“, sometimes followed by “I’ll never do it” is born in the minds of children. When looked at from this point of view, it is easy to understand the plummeting enthusiasm of so many young students at such an early stage. Some will be tempted to give up almost immediately following this initial loss of motivational ‘energy’ while others will continue to ‘plod along’ for weeks or months. Teachers would be well advised to anticipate, and proactively plan for this. Awareness of, and total acceptance of, the fact that the earliest encounters with instrumental playing are almost invariably discouraging for children is fundamental to the teacher’s understanding of their task. Consequently, the need to develop and deploy, on a regular basis, strategies to support their students in the face of such difficulties, will become an essential element of their day to day activity. This might make the ‘motivation curve’ begin to look more like the one in the following diagram, where the upward-pointing arrows represent the teacher’s support, encouragement and reassurance leading to a renewal of their students’ desire to succeed in mastering their instruments.

In cases where such support is not forthcoming; where there is a failure to effectively apply thought-through strategies for maintaining motivation, the eventual outcome will probably be that the students in question withdraw from lessons. Consider the following statistics, again from the ABRSM:

Figure 3: Reasons for Stopping Playing

Looking at the chart and adding the percentages together, we find that over three quarters (76%) of the students who gave up did so because they do not find the subject sufficiently interesting for it to take precedence over other activities or even to organise their time to accommodate it. As the same source, Making Music 2014, tells us;

“The primary reason children and adults stop learning is lack of interest in playing as well as competing pressures from school, work and other activities”.[ii]

What this all amounts to, however, is the simple fact that they were not sufficiently motivated to continue. Whilst it may be true that, in certain circumstances, students may genuinely lose interest, or find other activities that they would rather devote their time to, we would be well-advised not simply to accept withdrawals at face value. As has already been proposed, it is incumbent upon us all, as instrumental teachers, to examine closely and honestly, our own role in a process that leads to one or more of our students giving up playing, effectively depriving themselves of opportunities to enrich their lives in ways far beyond the realms of mere leisure activity or entertainment.

The nature of any skill is such that it can only be developed gradually and by way of practice: not by reading, not by memorising, but by doing. This inevitably leads to the truism that, to acquire proficiency in instrumental playing, one must play one’s instrument regularly and frequently – one has to practise. As has been seen, for a young beginner, the desire to do this is usually very strong initially but, in all but a few cases, the initial excitement and enthusiasm from taking hold of a beautiful instrument, which they know to be capable of producing beguiling and exciting sounds, is somewhat short-lived. As alluded to above, most parents know this, so before investing in instruments and tuition, they often express misgivings about the likelihood of their children quitting after a relatively short time. Teachers meet with their students on average once a week and are acutely aware that if this is all the playing their students do, there will be no meaningful progress. It is essential, therefore, that a major element of their activity during lessons is in ensuring that the students’ initial desire to play their instruments is maintained.

[i] Various. ‘Making Music 2014’, London. 2014: Associated Board of The Royal Schools of Music.

[ii] Ibid.