The traditional reliance on a notation-based approach to teaching elementary repertoire has turned most people’s early experience of instrumental playing into a process whereby a set of difficult and complex puzzles have to be solved. Only if the student can remember the letter names, the fingerings, the correct embouchure, etc., and the note values before finally managing to bring these together for a whole string of notes, will the result be recognisable as a tune. Not only is this frustrating for students, but in many cases, the greater part of the guidance they receive from their teachers comes in the form of reminders, corrections or admonitions. It is almost certain that most players at this stage leave their lessons with only the faintest aural impression with which to compare their own performance.

In order to enable beginners to play music that can mean something to them (for this it needs to be related to their previous experience) without getting ‘bogged down’ in solving notational problems, it is best if the teacher demonstrates a particular phrase, passage, note or technique first and then encourages the students to imitate. This bypasses the verbal, notational and conceptual maze the student would inevitably be caught up in otherwise. Think of that popular trick that children play on their friends or parents by asking them to describe a spiral. In most cases (probably 99% or more) the answer involves a gesture delineating a spiral and hardly any verbal explanation at all! In fact, most people find it extremely difficult to describe such a concept, and I suspect that an accurate explanation would be so complex in mathematical terms as to be largely incomprehensible to all except a few professors of mathematics! We, as instrumental teachers, can identify with, and learn quite a lot from, this!

So, in the early stages, simple phrases and later familiar tunes can be learned simply by the student observing and copying what the teacher does. The degree of accuracy and detail – in, for example, articulation, phrasing or nuance – that the student is able to introduce will be considerably more than if he/she is bogged down in note reading and the teacher can gradually demand more and more. By doing so he/she will be developing musicianship alongside technique.

The more striking a student’s experience of the excerpt in question; when played accurately with clear articulation and exemplary tone quality, the firmer will be the impression on which they are able to base their own attempts. A clear aural image of how the instrument should sound may only be built up if they repeatedly hear playing of a high standard during their lessons. The same principle applies to the music itself. If students are able clearly to recollect how the music they are learning is supposed to sound, their efforts away from the lesson are more likely to bear fruit (see also Excuse me, how do I get to Carnegie Hall?). To facilitate this, it is helpful to get them to sing the tunes they are studying as well as enabling them to hear them played correctly.

Seeing how an experienced player negotiates the often uncomfortable physical contortions associated with playing a particular instrument such as how to hold it while retaining satisfactory posture and relaxation, how to position fingers, set the embouchure etc, is every bit as critical. An intimate understanding of the nature of the interface between students’ bodies and their instruments will be developed all the more quickly if verbal instructions are reinforced visually at every available opportunity. Not only will this prove an invaluable aid to learning, but also, since a demonstration is so much more immediate than an explanation, it will help in making the most of the available lesson time. The resourceful teacher will take steps to supplement his or her demonstrations in lessons with recordings, be they audio or video – very easy since most students will be carrying a video camera and sound recorder in their pockets, in the form of a cell phone!

Conscientious students will find it of enormous value to have the opportunity to refer to these during their practice sessions at home. “One showing is worth a thousand tellings,” said Confucius. This particular fragment of wisdom could hardly have more relevance than to instrumental teaching.

In a teaching methodology that leaves notation completely on one side to begin with, the earliest materials to be learned will be short fragments or phrases copied from the teacher’s demonstrations. From here, it will be possible to ask the students to come up with their own fragments, having laid down some obvious ground rules concerning the speed, number of notes, etc. It is, of course, necessary to keep sight of the fact that the skills being taught at this stage are primarily those of instrumental technique.

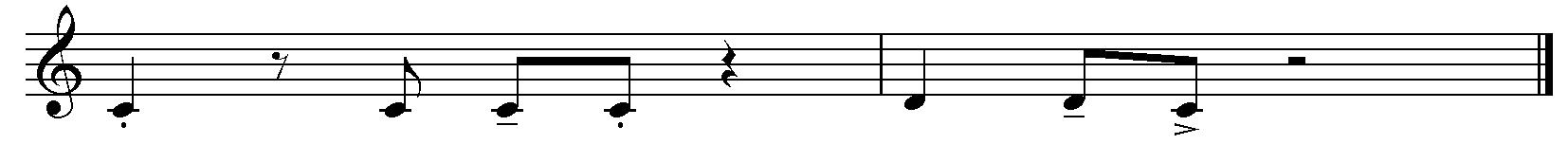

Depending on the instruments being taught, the very first fragments will vary from sustained and or repeated notes – possibly on a single pitch, to very simple melodic fragments employing two, three or more pitches. Much of this, by itself, may not be very exciting for most young students, so it is essential to create a musical context for these early ventures. Even the first efforts at sustained or repeated notes can be given an enormous ‘lift’ by adding an accompaniment, either on CD, electronic keyboard, computer or played on the piano by the teacher. Once the basic principles of technique have been grasped, it will be possible to introduce phrases with a little more rhythmic interest. Such a fragment might be along the following lines;

Example 1

With some guidance as to the notes to be used and to some basics ‘rules’ for example that the rhythm has to be similar, the student might respond with something like the following;

Example 2

Or, if the student is asked to reverse the order of the notes, this might become;

Example 3

If asked to devise a contrasting fragment using the same notes, he or she might produce something like this;

Example 4

It is not at all unusual for young students to come up with answering fragments such as these if they are given the opportunity and the necessary guidance. Again, they are able further to relate these to their experience in terms of rhythm and style if an accompaniment with a clear, strong beat, is provided.

Do note that the detailed articulations given here will only prove difficult for the student if he/she is asked to read them from notation. Copying the teacher’s articulation, having been encouraged to listen closely, is a completely different ‘ball game’ and it will demand a degree of expression in the playing from the outset.

So, if you have a keyboard with auto rhythms, why not try it now?

As fluency is gained, and technique extended to allow a greater range of notes, it will be possible to incorporate additional pitches and, therefore, intervals. However, the teacher will need to plan carefully to ensure that the fingering challenges presented by the rhythmic inventions are appropriate to the students’ stages of learning and that not all of the available notes are used in every phrase. From a learning point of view, the new pitches are best added one at a time, building gradually on what is familiar. With the availability of new pitches, it would be possible by way of introducing minor changes to transform existing material into something new. The example from above might be modified as follows;

Example 5

An answering phrase based on the previous examples might be along the lines of;

Example 6

This kind of work develops not only the essential instrumental skills of tone production, articulation etc but also allows fluency to come about quite rapidly. There is also a marked necessity for aural awareness and imagination, both of which can be called upon in increasing measure. Given the appealing musical environments that may be created by the use of CD or keyboard accompaniments they also provide the essential ingredients i.e. engagement, interest and motivation.

Having started by copying and then improvising short, manageable phrases, it will soon become necessary to develop these into something which the student recognises as music. Such recognition depends on the perception of a clear structure. The most basic means by which structure can be imposed upon improvised phrases are repetition, repetition with slight modification or by way of contrasting answering phrases. It will immediately be clear that most traditional musical forms e.g. binary, ternary, rondo etc comprise interplay of all three. By way of illustration, it will be useful to observe how the above examples clearly and easily open the way for the introduction of a simple binary structure with the order of the phrases being A-B-A-B (modified) as follows;

Example 7

Following this, you might add some dynamic contrasts and you can even use ‘musical’ words like ‘piano’, ‘forte’, ‘staccato’ etc, then you might introduce further contrasts such as ‘legato’ which in turn will involve developing technique in the case of most instruments.

As the work progresses, and the structure being developed become more complex, the necessity for a simple notational system as an aide-memoire (particularly for home practice) may well present itself. A fragment such as Example 1 above, only contains two pitches, so there is hardly any need for ‘green buses driving fast’ at this stage! Having first been improvised and then learned, it could be notated by the students in a manner similar to the following;

Example 8

At this stage, reference to notes by their letter names may be desirable – especially if associated with fingerings, so that C is “thumb or finger no. 1” (piano), “thumb and first three fingers down” (clarinet), or ‘open’ (trumpet).

Gradually, more lines can be introduced as the number of pitches in the student’s repertoire grows, until finally, a stave is being used.

Keep reading…

Robert Lennon’s book, Instrumental Music Teaching is packed with ideas and strategies, supported by research, to help you be the best teacher you can be!

Available in paperback or Kindle versions from Amazon or in PDF format, compatible with many eReader apps, here.

“A fantastic read.“